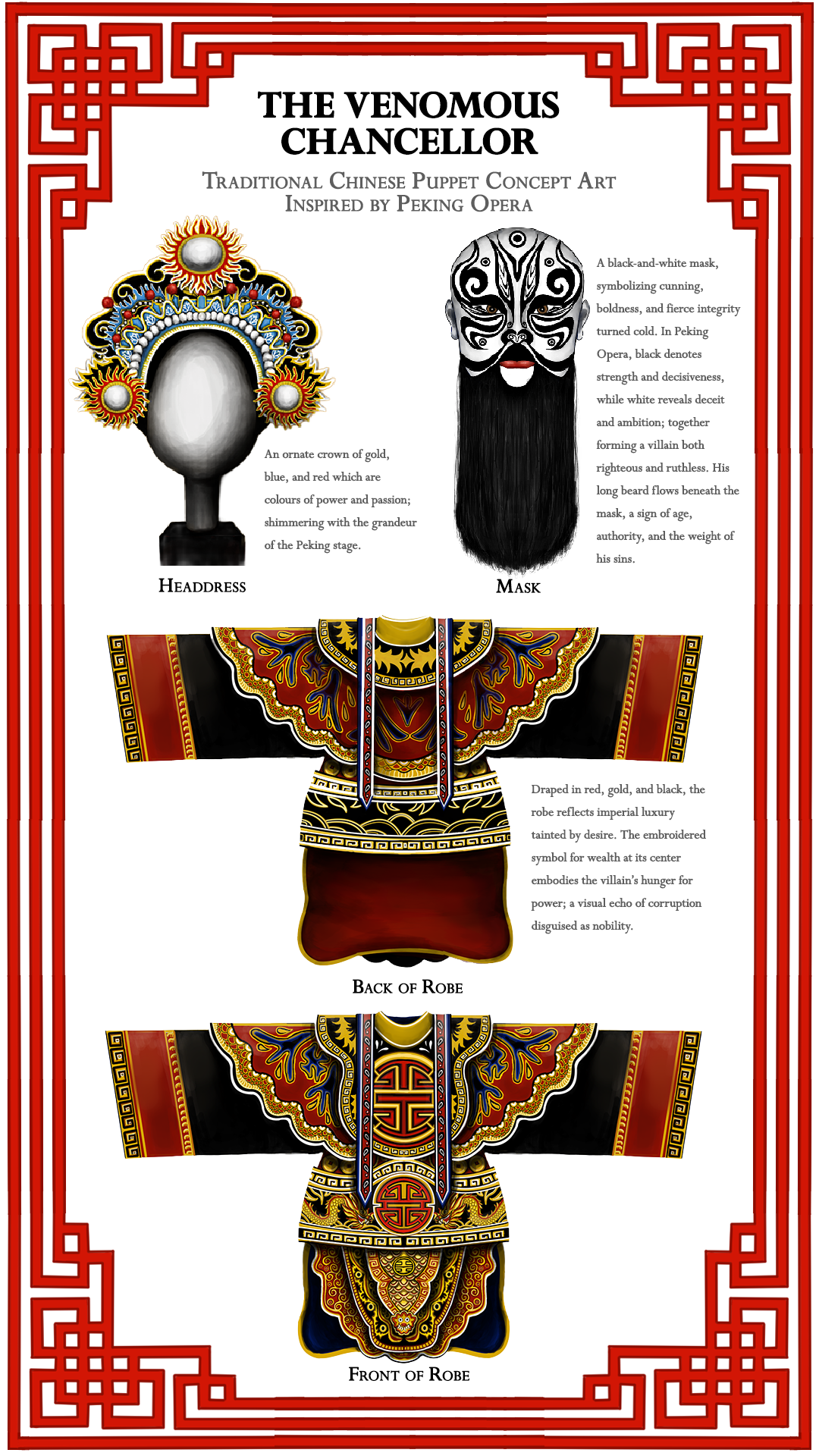

The Venomous Chancellor

The Venomous Chancellor is a concept art project developed for a hypothetical Chinese puppet show, a cultural reimagining of the Robin Hood legend. In this version, the story is set within a stylized interpretation of ancient China, where themes of justice, corruption, and rebellion unfold through the distinct artistry of traditional Peking opera aesthetics.

I designed The Venomous Chancellor as the primary antagonist, he is a cunning and morally corrupt official whose elaborate costume and exaggerated expressions convey both authority and deceit. The character’s visual design draws heavily from Peking opera color symbolism and puppet craftsmanship, incorporating sharp silhouettes and rich embroidery.

Qingdao Puppet Experience

In the summer of 2024, I had the incredible opportunity to travel to Qingdao, China, where I collaborated with students from Qingdao University of Science and Technology. This trip became a deep dive into the world of traditional Chinese puppetry, its artistry, and its philosophy.

Together, we visited a local puppet-making workshop, where I got to see first-hand how puppets are built, painted, and brought to life. Watching the artisans at work was mesmerizing. Every joint, costume layer, and carved expression served a storytelling purpose. Later, we saw a traditional puppet theatre performance, and it was magical. A beautifully handcrafted rod puppet, dressed in a flowing floral gown, danced gracefully across the stage to traditional Chinese music. The beauty and precision of this performance highlighted how deeply visual design, rhythm, and gesture intertwine within Chinese theatrical traditions. It felt like it was alive.

Through this experience, I came to understand that puppetry in China, much like human theatre, is a total art form: a synthesis of music, song, dialogue, dance, mime, martial arts, ritual, storytelling, and craftsmanship. Beyond entertainment, puppetry embodies philosophical and spiritual values, reflecting Chinese perspectives on morality, the soul, and the continuity between life and death. It serves not only as a means of artistic expression but also as a vessel for cultural memory and collective psychology.

History of Puppets

The deep historical roots of puppetry in China, tracing back to ancient funerary practices of the Shang and Zhou Dynasties. Archaeological discoveries show that early wooden and terracotta figurines, some articulated for movement, likely inspired later puppet traditions. These figures, placed in tombs to accompany the spirit in the afterlife, mark the origins of puppetry as both ritual and representation, a symbolic bridge between the living and the dead.

By the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), evidence shows that puppets were already used in festivals and ceremonies, evolving from sacred rituals into popular entertainment. Over time, new genres such as rod puppets, string marionettes, glove puppets, iron-rod puppets, and shadow puppets emerged, each with distinct regional styles and symbolic meanings. The art form continued to evolve through major dynasties:

Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE): A golden age of cross-cultural exchange, when Chinese puppetry absorbed influences from India and Central Asia. The period saw the creation of early mechanical puppets, demonstrating remarkable craftsmanship and technological innovation.

Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE): With urbanization came larger audiences and more sophisticated productions. Puppets appeared frequently in paintings, poetry, and festivals, reflecting their popularity in everyday life.

Yuan and Ming Dynasties (1271–1644 CE): Regional puppet styles flourished, each developing unique musical forms, dialects, and performance traditions. In Fujian province, the art reached exceptional refinement, particularly with string and glove puppetry, known for expressive movement and intricate costume detail.

Qing Dynasty (1644–1911 CE): Puppetry became more widely accessible, blending with the aesthetics of Peking opera—notably the jing (painted face) character type, which influenced costume design and visual storytelling.

Historically, puppeteers held a position of spiritual and cultural respect. Unlike actors, whose social status was traditionally low, puppeteers were sometimes seen as masters of ritual and wisdom, linked to Daoist and shamanic traditions. Their craft was believed to contain magical properties, symbolically animating the inanimate and giving life to moral allegory.

Even in modern China, puppetry remains a living art, adapting to new contexts while preserving its ritualistic and educational roots. Although globalization has changed the rural culture that once sustained it, the essence of Chinese puppetry endures as a mirror of history, philosophy, and the artistry of human imagination.

For me, this cultural and historical exploration profoundly shaped The Venomous Chancellor. It deepened my understanding of how visual design conveys morality and symbolism, how each colour, gesture, and material choice can reflect inner nature, status, and fate. The project became not only a creative reinterpretation of Robin Hood within a Chinese aesthetic, but also a reflection of my growing respect for an art form that continues to embody centuries of craft, storytelling, and spiritual expression.